|

|

|

|

|

RODENTS: Muskrats |

|

|

Fig. 1. Muskrat, Ondatra

zibethicus

Damage

Prevention and Control Methods Exclusion

-

Riprap the inside of a

pond dam face with rock, or slightly overbuild the

dam to certain specifications.

-

Cultural Methods and

Habitat Modification

-

Eliminate aquatic

vegetation as a food source.

-

Draw down farm ponds

during the winter months.

-

Frightening

-

Seldom effective in

controlling serious damage problems.

-

Repellents

-

None are registered.

-

Toxicants

-

Zinc phosphide.

-

Anticoagulants (state

registrations only).

-

Trapping

-

Body-gripping traps (Conibear®

No. 110 and others).

-

Leghold traps, No. 1,

1 1/2, or 2.

-

Where legal, homemade

“stove pipe” traps also are effective when properly

used.

-

Shooting

-

Effective in

eliminating some individuals.

-

Other Methods

-

Integrated pest

management.

Identification

The muskrat (Ondatra

zibethicus, Fig. 1) is the largest microtine rodent in

the United States. It spends its life in aquatic

habitats and is well adapted for swimming. Its large

hind feet are partially webbed, stiff hairs align the

toes (Fig. 2), and its laterally flattened tail is

almost as long as its body. The muskrat has a stocky

appearance, with small eyes and very short, rounded

ears. Its front feet, which are much smaller than its

hind feet, are adapted primarily for digging and

feeding.

The name muskrat, common

throughout the animal’s range, derives from the paired

perineal musk glands found beneath the skin at the

ventral base of the tail in both sexes. These musk

glands are used during the breeding season. Musk is

secreted on logs or other defecation areas, around

houses, bank dens, and trails on the bank to mark the

area.

The muskrat has an upper

and a lower pair of large, unrooted incisor teeth that

are continually sharpened against each other and are

well designed for gnawing and cutting vegetation. It has

a valvular mouth, which allows the lips to close behind

the incisors and enables the muskrat to gnaw while

submerged. With its tail used as a rudder and its

partially webbed hind feet propelling it in the water,

the muskrat can swim up to slightly faster than 3 miles

per hour (4.8 kph). When feeding, the muskrat often

swims backward to move to a more choice spot and can

stay underwater for as long as 20 minutes. Muskrat

activity is predominantly nocturnal and crespuscular,

but occasional activity may be observed during the day.

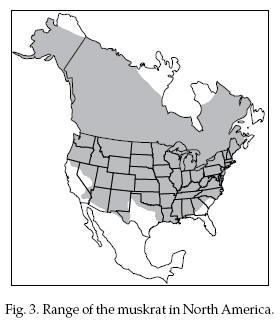

Range Range

The range of the muskrat

extends from near the Arctic Circle in the Yukon and the

Northwest Territories, down to the Gulf of Mexico, and

from the Aleutians east to Labrador and down the

Atlantic coast into Georgia (Fig. 3). The muskrat has

been introduced practically all over the world, and,

like most exotics, has sometimes caused severe damage as

well as ecological problems. Muskrats often cause

problems with ponds, levees, and crop culture, whether

introduced or native. Muskrats are found in most aquatic

habitats throughout the United States and Canada in

streams, ponds, wetlands, swamps, drainage ditches, and

lakes.

Habitat

Muskrats can live almost any place where

water and food are available year-round. This includes

streams, ponds, lakes, marshes, canals, roadside

ditches, swamps, beaver ponds, mine pits, and other

wetland areas. In shallow water areas with plentiful

vegetation, they use plant materials to construct

houses, generally conical in shape (Fig. 4). Elsewhere,

they prefer bank dens, and in many habitats, they

construct both bank dens and houses of vegetation. Both

the houses of vegetation and the bank burrows or dens

have several underwater entrances via “runs” or trails.

Muskrats often have feeding houses, platforms, and

chambers that are somewhat smaller than houses used for

dens.

Burrowing activity is the

source of the greatest damage caused by muskrats in much

of the United States. They damage pond dams, floating

styrofoam marinas, docks and boathouses, and lake

shorelines. In states where rice and aquaculture

operations are big business, muskrats can cause

extensive economic losses. They damage rice culture by

burrowing through or into levees as well as by eating

substantial amounts of rice and cutting it down for

building houses. In waterfowl marshes, population

irruptions can cause “eat-out” where aquatic vegetation

in large areas is virtually eliminated by muskrats. In

some locations, such as in the rice-growing areas of

Arkansas, muskrats move from overwintering habitat in

canals, drainage ditches, reservoirs, and streams to

make their summer homes nearby in flooded rice fields.

In aquaculture reservoirs, damage is primarily to levees

or pond banks, caused by burrowing.

Food Habits

Muskrats are primarily herbivores. They will

eat almost any aquatic vegetation as well as some field

crops grown adjacent to suitable habitat. Some of the

preferred natural foods include cattail, pickerelweed,

bulrush, smartweed, duck potato, horsetail, water lily,

sedges, young willow regeneration, and other aquatics.

Crops that are occasionally damaged include corn,

soybeans, wheat, oats, grain sorghum, and sugarcane.

Rice grown as a flooded crop is a common muskrat food.

It is not uncommon, however, to see muskrats subsisting

primarily on upland vegetation such as bermuda grass,

clover, johnsongrass, and orchard grass where planted or

growing on or around farm pond dams.

Although primarily

herbivores, muskrats will also feed on crayfish,

mussels, turtles, frogs, and fish in ponds where

vegetation is scarce. In some aquaculture industry

areas, this feeding habit should be studied, as it may

differ significantly from normal feeding activity and

can cause economic loss.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Muskrats generally have a small home range

but are rather territorial, and during breeding seasons

some dispersals are common. The apparent intent of those

leaving their range is to establish new breeding

territories. Dispersal of males, along with young that

are just reaching sexual maturity, seems to begin in the

spring. Dispersal is also associated with population

densities and population cycles. These population cycles

vary from 5 years in some parts of North America to 10

years in others. Population levels can be impacted by

food availability and accessibility.

Both male and female

muskrats become more aggressive during the breeding

season to defend their territories. Copulation usually

takes place while submerged. The young generally are

born between 25 and 30 days later in a house or bank

den, where they are cared for chiefly by the female. In

the southern states, some females may have as many as 6

litters per year. Litters may contain as many as 15, but

generally average between 4 and 8 young. It has been

reported that 2 to 3 litters per female per year is

average in the Great Plains. This capability affords the

potential for a prolific production of young. Young may

be produced any month of the year. In Arkansas, the peak

breeding periods are during November and March. Most of

the young, however, are produced from October until

April. Some are produced in the summer and early fall

months, but not as many as in winter months. The period

of highest productivity reported for the Great Plains is

late April through early May. In the northern parts of

its range, usually only 2 litters per year are produced

between March and September.

Young muskrats are

especially vulnerable to predation by owls, hawks,

raccoons, mink, foxes, coyotes, and — in the southern

states — even largemouth bass and snapping turtles. The

young are also occasionally killed by adult muskrats.

Adult muskrats may also be subject to predation, but

rarely in numbers that would significantly alter

populations. Predation cannot be depended upon to solve

damage problems caused by muskrats.

Damage and Damage Identification

Damage caused by muskrats

is primarily due to their burrowing activity. Burrowing

may not be readily evident until serious damage has

occurred. One way to observe early burrowing in farm

ponds or reservoirs is to walk along the edge of the dam

or shorelines when the water is clear and look for

“runs” or trails from just below the normal water

surface to as deep as 3 feet (91 cm). If no burrow

entrances are observed, look for droppings along the

bank or on logs or structures a muskrat can easily climb

upon. If the pond can be drawn down from 1 1/2 to 3 feet

(46 to 91 cm) each winter, muskrat burrows will be

exposed, just as they would during extended drought

periods. Any burrows found in the dam should be filled,

tamped in, and covered with rock to avoid possible

washout or, if livestock are using the pond, to prevent

injury to a foot or leg.

Where damage is occurring

to a crop, plant cutting is generally evident. In

aquaculture reservoirs generally maintained without lush

aquatic vegetation, muskrat runs and burrows or remains

of mussels, crayfish, or fish along with other muskrat

signs (tracks or droppings) are generally easy to

observe.

Legal Status

Muskrats nationwide for

many years were known as the most valuable furbearing

mammal — not in price per pelt, but in total numbers

taken. Each state fish and wildlife agency has rules and

regulations regarding the taking of muskrats. Where the

animal causes significant economic losses, some states

allow the landowner to trap and/or use toxic baits

throughout the year. Other states prohibit taking

muskrats by any means except during the trapping season.

Check existing state wildlife regulations annually

before attempting to remove muskrats.

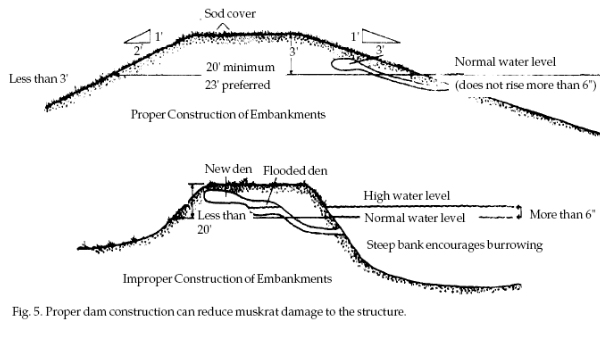

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Muskrats in some

situations can be excluded or prevented from digging

into farm pond dams through stone rip-rapping of the

dam. Serious damage often can be prevented, if

anticipated, by constructing dams to the following

specifications: the inside face of the dam should be

built at a 3 to 1 slope; the outer face of the dam at a

2 to 1 slope with a top width of not less than 8 feet

(2.4 m), preferably 10 to 12 feet (3 to 3.6 m). The

normal water level in the pond should be at least 3 feet

(91 cm) below the top of the dam and the spillway should

be wide enough that heavy rainfalls will not increase

the level of the water for any length of time (Fig. 5).

These specifications are often referred to as

overbuilding, but they will generally prevent serious

damage from burrowing muskrats. Other methods of

exclusion can include the use of fencing in certain

situations where muskrats may be leaving a pond or lake

to cut valuable garden plants or crops.

Cultural Methods and

Habitat Modification

The best ways to modify habitat are to eliminate

aquatic or other suitable foods eaten by muskrats, and

where possible, to construct farm pond dams to

previously suggested specifications. If farm pond dams

or levees are being damaged, one of the ways that damage

can be reduced is to draw the pond down at least 2 feet

(61 cm) below normal levels during the winter. Then fill

dens, burrows, and runs and rip-rap the dam with stone.

Once the water is drawn down, trap or otherwise remove

all muskrats.

Frightening Devices

Gunfire will frighten muskrats, especially those

that get hit, but it is not effective in scaring the

animals away from occupied habitat. No conventional

frightening devices are effective.

Repellents

No repellents currently are registered for muskrats,

and none are known to be effective, practical, and

environmentally safe.

Toxicants

The only toxicant federally registered for muskrat

control is zinc phosphide at 63% concentrate. It is a

Restricted Use Pesticide for making baits. Zinc

phosphide baits for muskrats generally are made by

applying a vegetable oil sticker to cubes of apples,

sweet potatoes, or carrots; sprinkling on the toxicant;

and mixing thoroughly. The bait is then placed on

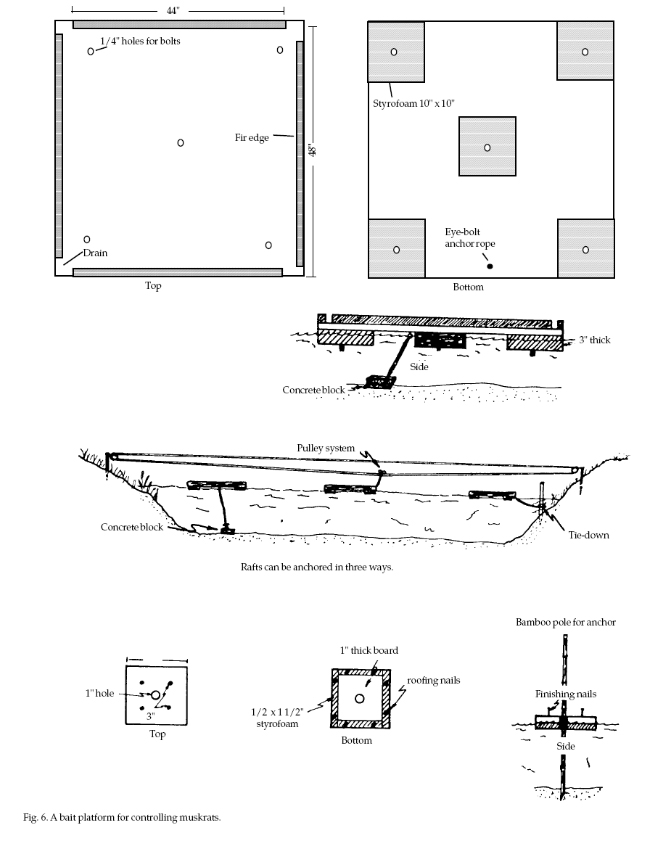

floating platforms (Fig. 6), in burrow entrances, or on

feeding houses. Use caution when mixing and applying

baits treated with zinc phosphide. Carefully follow

instructions on the zinc phosphide container before

using.

Some states have obtained

state registrations for use of anticoagulant baits such

as pivalyl, warfarin, diphacinone, and chlorophacinone.

These materials have proven effective, species

selective, practical, and environmentally safe in field

applications to control muskrats. Apparently there is

not sufficient demand or research available to consider

federal registration of anticoagulants for muskrats.

These same first-generation anticoagulants are, however,

federally registered for use in control of commensal

rodents in and around buildings, and for some use in

field situations for rodent control.

Use of the anticoagulant

baits, where registered, is in the form of a

paraffinized “lollipop” made of grain, pesticide, and

melted paraffin. It is placed in burrows or feeding

houses. The anticoagulant baits also can be used as a

grain mixture in floating bait boxes.

Fumigants

No fumigants are currently registered for muskrat

control.

Trapping

There have probably been more traps sold for

catching muskrats than for catching any other furbearing

species. A number of innovative traps have been

constructed for both live trapping and killing muskrats,

such as barrel, box, and stovepipe traps.

The most effective and

commonly used types of traps for muskrats, however, are

the Conibear®-type No. 110 (Fig. 7) and leghold types

such as the long spring No. 1, 1 1/2, or 2 (Fig. 8) and

comparable coil spring traps. Each type has places and

situations where one might be more effective than

another. The Conibear®-type, No. 110 is a preferred

choice because it is as effective in 6 inches (15 cm) of

water as at any deeper level. It kills the muskrat

almost instantly, thus preventing escapes. All that is

needed to make this set is a trap stake and trap.

Muskrats are probably the

easiest aquatic furbearer to trap. In most cases where

the run or burrow entrance is in 2 feet (61 cm) of water

or more, even a leghold trap requires only a forked

stake to make a drowning set. A trap set in the run, the

house or den entrance, or even under a feeding house,

will usually catch a muskrat in 1 or 2 nights. As a test

of trap efficiency, this author once set 36 Conibear®-type

No. 110 traps in a 100 acre (40-ha) rice field and 24

No. 1 1/2 leghold traps in a nearby 60-acre (24 ha)

minnow pond on a July day. The next day 55 muskrats were

removed. The remaining traps had not been tripped.

Obviously, both of these areas held high populations of

muskrats and Fig. 10. Pole set neither had been

subjected to recent control efforts. Results were 93.3%

effectiveness with the Conibear®-type, 87.5%

effectiveness with the leghold traps, and 100% catch per

traps tripped.

The most effective sets

are those placed in “runs” or trails where the muskrat’s

hind feet scour out a path into the bottom from repeated

trips into and out of the den. These runs or trails can

be seen in clear water, or can be felt underwater with

hands or feet. Which runs are being used and which are

alternate entrances can usually be discerned by the

compaction of the bottom of the run. Place the trap as

close to the den entrance as possible without

restricting trap movement (Fig. 9).

Other productive sets are

pole sets, under ice sets (Figs. 10 and 11), and culvert

sets. Other traps also can be used effectively in some

situations.

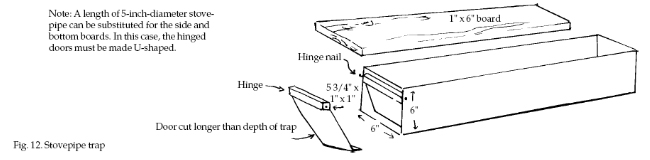

The stovepipe trap (Fig.

12) is very effective in farm ponds, rice fields, and

marshes — where it is legal. This type of trap requires

more time and effort to set, but can be very effective

if the correct size is used. The trap is cheap, simple,

and easy to make; however, to my knowledge, it is not

available commercially. If properly set in a well-used

den entrance, it will make multiple catches.

The stovepipe trap has the

potential to catch from two to four muskrats on the

first night if set in the primary den entrance. The trap

is cumbersome to carry around, however, and must be

staked down properly and set right up against the den

entrance to be most effective. The traps can be easily

made from stovepipe, as the name implies, but some of

the most effective versions are variations. An example

is a sheet metal, 6 x 6-inch (15 x 15-cm) rectangular

box, 30 to 36 inches (76 to 91 cm) long with heavy-gauge

hardware cloth or welded wire doors. The doors are

hinged at the top to allow easy entry from either end,

but no escape out of the box. Death from drowning occurs

in a short time. The trap design also allows for

multiple catches. Its flat bottom works well on most

pond bottoms and in flooded fields or marshes, and it is

easy to keep staked down in place. Such a trap can be

made in most farm shops in a few minutes. All sets

should be checked daily.

Trapping muskrats during

the winter furbearer season can be an enjoyable

past-time and even profitable where prices for pelts

range from $2.00 to $8.00 each. Price differences depend

on whether pelts are sold “in the round” or skinned and

stretched. Many people supplement their income by

trapping, and muskrats are one of the prime targets for

most beginners learning to trap. Therefore, unless

muskrats are causing serious damage, they should be

managed like other wildlife species to provide a

sustained annual yield. Unfortunately, when fur prices

for muskrats are down to less than $2.00 each, interest

in trapping for fur seems to decline. However, in damage

situations, it may be feasible to supplement fur prices

to keep populations in check.

Shooting

Where it can be done safely, shooting may eliminate

one or two individuals in a small farm pond.

Concentrated efforts must be made at dusk and during the

first hours of light in the early morning. Muskrats shot

in the water rarely can be saved for the pelt and/or

meat.

Other Methods

Although a variety of other methods are often

employed in trying to control muskrat damage, a

combination of trapping and proper use of toxicants is

the most effective means in most situations. In

situations where more extensive damage is occurring, it

may be useful to employ an integrated pest management

approach: (1) modify the habitat by removing available

food (vegetation); (2) concentrate efforts to reduce the

breeding population during winter months while muskrats

are concentrated in overwintering habitat; and (3) use

both registered toxicants and trapping in combination

with the above methods.

Economics of Damage and Control

Assessment of the amount

of damage being caused and the cost of prevention and

control measures should be made before undertaking a

control program. Sometimes this can be easily done by

the landowner or manager through visual inspection and

knowledge of crop value or potential loss and

reconstruction or replacement costs. Other situations

are more difficult to assess. For example, what is the

economic value of frustration and loss of a truckload of

minnows and/or fish after a truck has fallen through the

levee into burrowed-out muskrat dens? Or how do you

evaluate the loss of a farm pond dam or levee and water

behind it from an aquaculture operation where hundreds

of thousands of pounds of fish are being grown? Rice

farmers in the mid-South or in California must often

pump extra, costly irrigation water and shovel levees

every day because of muskrat damage. The expense of

trapping or other control measures may prove

cost-effective if damage is anticipated.

Obviously, the assessments

are different in each case. The estimate of economic

loss and repair costs, for example, for rebuilding

levees, replacing drain pipes, and other measures, must

be compared to the estimated cost of prevention and/or

control efforts.

Economic loss to muskrat

damage can be very high in some areas, particularly in

rice and aquaculture producing areas. In some states

damage may be as much as $1 million per year. Totals in

four states (Arkansas, California, Louisiana, and

Mississippi) exceed losses throughout the rest of the

nation.

Elsewhere, economic losses

because of muskrat damage may be rather limited and

confined primarily to burrowing in farm pond dams. In

such limited cases, the value of the muskrat population

may outweigh the cost of the damage.

Muskrat meat has been

commonly used for human consumption and in some areas

called by names, such as “marsh rabbit.” A valuable

resource, it is delicious when properly taken care of in

the field and in the kitchen. Many wild game or outdoor

cookbooks have one or more recipes devoted to “marsh

rabbit.” Care should be taken in cleaning muskrats

because of diseases mentioned earlier.

Muskrat pelts processed

annually are valued in the millions of dollars, even

with low prices; thus the animal is certainly worthy of

management consideration. It obviously has other values

just by its place in the food chain.

Acknowledgments

For Additional Most of the information in

this chapter was obtained from experience gained in

Alabama, where as a youngster I trapped muskrats and

other furbearers to sell, and in Arkansas where muskrat

control is a serious economic problem. Colleagues in the

Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service, and especially

county extension agents, provided the opportunity and

background for obtaining this information. The Arkansas

Farm Bureau, many rice farmers, fish farmers, and other

private landowners/ managers, as well as the Arkansas

Game and Fish Commission and the Arkansas State Plant

Board, were also important to the development of this

information.

Figures 1 through 4 from

Schwartz and Schwartz (1981).

Figure 5 from Henderson

(1980).

Figure 6 from J. Evans

(1970), About Nutria and their Control, USDI, Bureau of

Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, Resour. Pub. No. 86. 65

pp.

Figures 7 and 8 from

Miller (1976).

Figures 9, 10, and 11 from

Manitoba Trapper Education publications.

Figure 12 by Jill Sack

Johnson.

Information Miller, J. E.

1972. Muskrat and beaver control. Proc. First Nat. Ext.

Wildl. Workshop, Estes Park, Colorado, pp. 35-37.

Miller, J. E. 1974.

Muskrat control and damage prevention. Proc. Vertebr.

Pest Conf. 6:85-90.

Miller, J. E. 1976.

Muskrat control. Arkansas Coop. Ext. Serv., Little Rock.

Leaflet No. 436.

Nowak, R. M. 1991.

Walker’s mammals of the world. 5th ed. The Johns Hopkins

Univ. Press. Baltimore, Maryland. 1629 pp.

Schwartz, C. W., and E. R.

Schwartz. 1981. The wild mammals of Missouri, rev. ed.

Univ. Missouri Press, Columbia. 356 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom; Robert M. Timm; Gary E.

Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln

United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control

Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

05/17/2006

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|