|

|

|

|

|

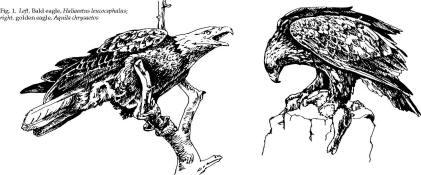

BIRDS: Eagles |

|

|

Identification

Eagles are the largest

bird of prey in North America. When hatched, eaglets

have thick, light-colored down that is replaced with

dark feathers within 5 to 6 weeks. Eagles have long

sharp talons by which they capture and kill prey

animals. The tarsi (lower legs) are feathered to the

toes on golden eagles but are bare on bald eagles (Fig.

2).

Golden eagles weigh from 7

to 13 pounds (3 to 6 kg) as adults and have a wingspread

of 6 to 7 1/2 feet (1.8 to 2.3 m); females are about

one-third larger than males.

The plumage color of

golden eagles changes with age. Birds in their first

year are predominantly dark brown, with considerable

areas of white on the underside of their wing flight

feathers. The tail has a broad white band with a dark

terminal band at the tip. The back of the neck may or

may not appear gold or bronze, depending upon light

conditions and the individual bird. This color is what

gave the golden eagle its common name. Adult eagles are

dark brown or bronze (Figs. 2 and 3).

Bald eagles weigh from 9

to 15 pounds (4 to 7 kg) as adults and have a wingspread

of 7 to 8 feet (2.1 to 2.4 m). As in golden eagles,

females are about one-third larger than males.

Bald eagle plumage color

also changes with age. Juvenile bald eagles generally

are mottled brown or nearly black and resemble adult

golden eagles. These juveniles have no distinct white

patches. Their tail and wings are mottled brown and

white on the underside in contrast to the characteristic

white patches under the wings and the white-banded tail

of juvenile golden eagles. Although adult bald eagles of

both sexes have the white head and tail, they do not

develop these characteristics until they are 4 to 5

years of age or older (Figs. 2 and 3).

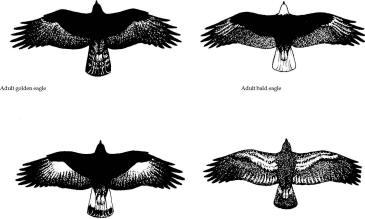

Fig. 2. Characteristics of

golden and bald eagles. Fig. 3. Golden and bald eagles

in flight. Immature golden eagle and bald eagle

Range

Golden eagles in North

America occur in greatest numbers from Alaska southward

throughout the mountain and intermountain regions of the

West and into Mexico. They occur in lower numbers to the

east across Canada, the Great Lakes states, and the

Appalachian Mountains of the eastern United States.

Bald eagles have a similar

range but tend to be most common near the seacoasts and

other large bodies of water. In winter they may

concentrate along major lakes and rivers. By far the

greatest concentration of bald eagles is in Alaska,

along large rivers and the coast.

Habitat

Eagles frequent a wide

variety of habitats. Golden eagles seem to prefer the

rough broken terrain of foothills and mountains,

valleys, rimrocks, and escarpments. They commonly hunt

the adjacent plains for food.

Bald eagles seem to prefer

timbered areas along coasts, large lakes, and rivers,

but they also occupy other areas.

Eagles often abandon

habitat that is subject to intensive human activity and

move to more remote areas.

Food Habits

Although regional and

seasonal differences in food habits exist, golden eagle

prey consists mostly of small mammals such as

jackrabbits, cottontails, prairie dogs, and ground

squirrels. A variety of birds and reptiles also have

been recorded as prey. Nesting pairs or concentrations

of juvenile birds can be a major cause of predation on

local game bird populations. Golden eagles also readily

eat carrion.

Golden eagles sometimes

attack large mammals; deer and pronghorns of all ages

have been observed being attacked or killed by eagles.

Records also exist of bighorn sheep, coyotes, bobcats,

and foxes being killed. Occasionally, golden eagles kill

calves, sheep, or goats. However, attacks on animals

that weigh more than 30 to 40 pounds (14 to 18 kg) are

uncommon. Where golden eagles prey on domestic animals,

they usually take lambs and kids, but some become

persistent predators of domestic livestock as large as

500 pounds (227 kg).

Bald eagles rely heavily

on fish and carrion where available. They readily adapt,

however, to preying on waterfowl, other birds, rabbits,

and other small mammals. They also occasionally kill

adult deer, pronghorns, and calves. At times, some may

prey repeatedly on domestic sheep and goats, primarily

young lambs and kids.

Experiments with captive

eagles indicate that adults require about 3/4 pound (1/3

kg) of meat per day to maintain their weight; young,

growing eagles require much more food. Accounts of the

weight that an eagle can carry in flight often have been

misstated. Experiments indicate that without wind to

assist them even large eagles cannot take off from flat

ground with more than 5 or 6 pounds (2 to 3 kg) in their

talons. Eagles flying into the wind and taking prey from

hillsides, however, sometimes carry animals of twice

those weights for considerable distances.

General

Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior Nesting Behavior

Eagle courtship displays

consist of a series of “roller coaster” dives and other

aerial maneuvers. These characteristic maneuvers may be

seen nearly any time of the year, but are most common

just before and during the late winter breeding season.

Aerial displays made during other seasons may serve to

identify territorial boundaries and maintain pair bonds

between adults.

Eagle nests of sticks and

twigs are built either on cliffs or in trees. Nests can

be very large, sometimes up to 8 feet (2.4 m) wide and

deep. The same nests may be used several years, becoming

larger as new material is added each year. Eagles

usually have several nests in a vicinity and may use

alternate sites.

Nesting can begin as early

as February in the south and as late as June in the

north. At nesting time, an adult pair builds new nests

or repairs old ones. Often, a single pair will build or

repair two or three nests during a single season. These

alternate nests are legally defined as “active” and are

protected by law. The nesting territory of golden eagles

varies from about 3 to 65 square miles (8 to 168 km2)

per pair.

Bald eagles seem less

antagonistic to other nesting pairs, and their nesting

territories, typically near water, may be much smaller.

Studies in Alaska have shown that bald eagle nests may

be spaced as closely as 1/4 mile (0.4 km) apart along

rivers, with nesting territories as small as 30 to 40

acres (12 to 16 ha) in some cases. This may be due to

more plentiful food near water.

Usually, 2 (1 to 3) white

or mottled brownish eggs are laid after nesting behavior

begins. The eggs hatch after a 35- to 45-day incubation

period. Both adults hunt and secure food for the young,

with the female doing most of the incubating, feeding,

and brooding. Young eagles become strong enough to tear

meat apart by 50 days of age. They are fully feathered

and ready to leave the nest 65 to 70 days after

hatching. Although the young are as large as the adult

birds at this time, their parents may continue to

provide them with food and protection for as long as 3

months after they leave the nest.

Not all eagle eggs hatch,

and the death rate of young eagles, as in other birds of

prey, is high. Young eagles are antagonistic toward each

other and the stronger often kills or causes the weaker

to die of starvation. Losses due to exposure, diseases,

parasites, and predation occur while the young are still

in the nest. Up to 75% of the young eagles die during

their first year due to starvation, disease, and causes

directly or indirectly associated with humans.

Illegal shooting,

chemicals, trapping, and power line electrocutions

account for a large number of eagle fatalities. Injuries

resulting from accidents such as flying into power lines

or being hit by vehicles while feeding on road-killed

animals also occur.

Dispersal and Migration

Juvenile golden eagles

leave the nesting territory as early as May in the

Southwest and as late as October or November in the

North. Many of the golden eagles that breed in the

northern United States and Canada migrate south for the

winter. They arrive in the southwestern United States as

early as October and reach peak numbers in December and

January in Texas and February and March in New Mexico

before migrating back north. Only resident birds remain

by late May. Golden eagles breeding in the more

temperate climates south of Canada often remain in the

same region year-round. Many northern golden eagles

migrate through areas occupied by resident eagles to

areas farther south.

Bald eagles usually are

found in coastal areas, along lakes and rivers, and on

mountain ridges. Usually, they are seen soaring or

sitting on commanding snags along bluffs or shores.

Pairs sometimes are observed together. After the nesting

season, they may congregate in areas where food is more

readily available, and then large numbers may roost in

the same tree. Immature birds also may roost together

during the winter.

Bald eagles will winter as

far north as open water and food are available,

migrating out of more northerly nesting areas. Returns

from banded bald eagles indicate that birds that nest in

Florida often migrate to the northeastern states and

southern Canada in midsummer and return in early fall.

Returns from birds banded in Saskatchewan indicate that

some move as far south as Texas and Arizona.

Eagle Populations

Research indicates that

golden eagles are maintaining static populations in

areas undisturbed by humans. The wintering population

south of Canada is estimated at 63,000 birds. Aerial

surveys conducted by the USFWS in 12 western states show

average densities of about 10 golden eagles per 100

square miles (4/100 km2) in midwinter study areas.

Golden eagles also winter in parts of Alaska, Canada,

and Mexico; however, the number in this latter group

would not likely exceed 10,000 birds.

Current population survey

information indicates a sizable and healthy population

of golden eagles in the western states. The current

breeding population for 17 western states is estimated

at 17,000 to 20,000 breeding pairs. Information

indicates a slight decline in the western population as

a whole, with drastic declines in some specific areas

associated with increased human activity.

Bald eagles occur across

the continent from northern Alaska to Newfoundland, and

south to southern Florida and Baja California. They are

found on Bering Island and the Aleutian Islands. Two

subspecies are recognized: the southern bald eagle (H.

l. leucocephalus) and the northern bald eagle (H. l.

alascans). The primary difference in appearance is size,

the northern race being larger and heavier. There is a

gradual increase in size from south to north.

The northern bald eagle

population in Alaska is estimated at 35,000 to 40,000.

In 1989, the breeding population of bald eagles in the

continental United States (excluding Alaska) was

estimated to be about 2,673 pairs. This estimate

included both races. The nationwide January eagle count

sponsored by the National Audubon Society indicated

about 3,700 birds each year from 1961 through 1966. The

annual midwinter counts coordinated by the National

Wildlife Federation since 1979 have ranged from about

9,000 birds to more than 13,000 in the contiguous 48

states. In 1989, 11,610 bald eagles were counted in key

wintering areas. The 1989 count does not represent a

comprehensive national count, so it is not directly

comparable to earlier counts. These January counts

indicated four areas of greatest abundance nationwide:

the upper half of the Mississippi Valley, the Northwest

(Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana), Florida, and

the Chesapeake Bay area.

Damage and Damage Identification

Golden eagles are more

likely to prey on livestock than are bald eagles. Both

species readily feed on livestock carrion and carcasses

left by foxes and coyotes, although some individuals

prefer live prey to carrion. Eagles are efficient

predators and can cause severe losses of young

livestock, particularly where concentrations of eagles

exist. Generally, they prey on young animals, primarily

lambs and kids, although they are capable of killing

adults. Eagles also take young deer and pronghorns, as

well as some adults.

Eagles have three front

toes opposing the hind toe, or hallux, on each foot. The

front talons normally leave wounds 1 to 3 inches (2.5 to

7.5 cm) apart, with the wound from the hallux 4 to 6

inches (10-15 cm) from the wound made by the middle

front talon. On animals the size of small lambs and

kids, fewer than four talon wounds may be found, one

made by the hallux and one or two by the opposing

talons. Talon punctures typically are deeper than those

caused by canine teeth and somewhat triangular or

oblong. Crushing between the wounds usually is not

found, although compression fractures of the skulls of

small animals may occur from an eagle’s grip. Bruises

from their grip are relatively common.

Eagles seize small lambs

and kids anywhere on the head, neck, or body, frequently

grasping from the front or side. They usually kill adult

animals, or lambs and kids weighing 25 pounds (11 kg) or

more, by multiple talon stabs into the upper ribs and

back. Their feet and talons are well adapted to closing

around the backbone, with the talons puncturing large

internal arteries, frequently the aorta in front of the

kidneys. The major cause of death is shock produced by

massive internal hemorrhage from punctured arteries or

collapse of the lungs when the rib cage is punctured.

Eagles also may simply seize young lambs, kids, or fawns

and begin feeding, causing the prey to die from shock

and loss of blood as it is eviscerated.

Eagles skin out carcasses,

turning the hide inside out while leaving much of the

skeleton intact, with the lower legs and skull still

joined to the hide. On very young animals, however, the

ribs often are neatly clipped off close to the backbone

and eaten. Eagles frequently do not eat the breast bone,

but some clip off and eat the lower jaw, nose, and ears.

Quite often, they remove the palate and floor pan of the

skull and eat the brain. They may clean all major

hemorrhages off the skin, leaving very little evidence

of the cause of death, even though there may be many

talon punctures in the skin. Ears, tendons, and other

tissues are sheared off cleanly by the eagle’s beak.

Larger carcasses heavily

fed on by eagles may have the skin turned inside out

with the skull, backbone, ribs, and leg bones left

intact, but with nearly all flesh and viscera missing.

The rumen normally is not eaten. Eagles may defecate

around a carcass, leaving characteristic white streaks

of feces on the soil. Their tracks may be visible in

soft or dusty soil. Small downy feathers often are

evident on vegetation where eagles have fed.

Legal Status

Both bald and golden

eagles and their nests and nest sites are protected by

the federal Bald Eagle Protection Act and state

regulations. In June 1940, legislation was passed that

outlawed killing, possessing, selling, or trading any

live or dead bald eagle, or any part of a bald eagle,

including feathers, eggs, and nests. In 1962, the same

protection was afforded the golden eagle. Provisions in

these laws allow specific permits to be issued by the US

Department of Interior for the taking of eagles or their

parts for scientific research, for exhibitions and

Indian religious purposes, and for control of predation

to domestic livestock (50 CFR, Part 22). Permits for

control of eagles to prevent or reduce predation on

livestock, however, have not been issued by the US

Department of Interior since 1970. Also, regulations

promulgated by the Secretary of Interior under authority

of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (as amended)

prohibit “taking” of an endangered species, such as bald

eagles. Because golden eagles also are protected, they

too cannot be “taken.” Congress has defined the term

take as follows: “to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot,

wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to

engage in any such conduct.”

A depredation permit from

the US Department of Interior is required to carry out

any eagle damage control activities. This requires a

formal consultation and biological assessment under

Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act for bald eagles.

At present, permits to take, harass, or scare

depredating golden eagles are issued routinely to the

western Regional Director of the USDA-APHIS-ADC by the

USFWS. Only USDA-APHIS-ADC personnel are permitted to

engage in eagle damage control activity under such

permits.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Eagles rarely attack livestock around buildings or

pens. Therefore, livestock confined in buildings or pens

of 1 to 2 acres (1/2 to 1 ha) usually are safe from

eagles. Fences, however, are no constraint to eagles;

livestock must be protected by other means.

Cultural Methods and

Habitat Modification

A common practice for many sheep and goat producers

is to avoid use of pastures where predation is severe

until lambs and kids are several weeks old. This

practice may reduce exposure of individual flocks or

herds to predation, but it is not always effective. It

may, however, cause predators to shift their attention

to livestock owned by other operators.

Eagles prefer relatively

open areas in which to take their prey. Lambs and kids

are much less vulnerable to eagle predation in brushy

and wooded areas. While use of such pastures may not

completely prevent eagle predation, it may help to

protect lambs and kids up to 4 to 6 weeks of age.

Predation by eagles is seldom a problem after lambs and

kids have reached 6 weeks of age.

Herding of livestock,

where feasible, usually will reduce eagle predation

because humans tend to frighten eagles. Herding may be

only partially effective, however, because eagles, like

other predators, adapt to existing conditions.

Shifting the lambing and

kidding seasons to an earlier or later period may also

help to reduce or prevent eagle predation, but the

decision must be based on the availability of pasture,

plant phenology, season and weather, availability of

labor, marketing constraints, and other considerations.

In some areas, such a shift may cause increased exposure

of young livestock to other predator species.

Shed lambing and kidding

is effective in preventing eagle predation during the

confinement period. Its limitations include the

availability of space, the quality and costs of feed

necessary to ensure and maintain milk production for

lambs and kids, and the length of confinement. Unless

the young are confined up to a month or more, shed

lambing and kidding will provide protection when the

chance of eagle predation is lowest. Eagles generally

take older lambs or kids that are running and playing

some distance from flocks, not the younger ones, who

usually stay close to their mother and within the flock.

Predation is most severe on young that are at least 2 to

4 weeks of age. Confinement of sheep and goats also may

be a very costly management decision for forage

utilization where high quality forage is available in

pastures and weather does not present a constraint to

the use of that forage.

Carrion removal may help

limit the size of local eagle populations. Eliminating

the eagles’ food source may force a potential problem to

move elsewhere. It may, however, encourage the eagles to

kill lambs or kids. If eagles depend heavily on carrion

in an area where young livestock are to be protected,

the eagles must either have an alternate food source or

be persuaded to move.

Frightening

Little information is available on the effects of

guard dogs to prevent eagle predation. Some dogs,

including breeds other than guard dogs, will chase birds. They

would probably be more effective in protecting sheep or

goats in small pastures than in large pastures and open

range conditions, particularly where livestock are

spread over large areas.

breeds other than guard dogs, will chase birds. They

would probably be more effective in protecting sheep or

goats in small pastures than in large pastures and open

range conditions, particularly where livestock are

spread over large areas.

Sonic devices have been

tested and show little benefit in preventing or reducing

eagle predation.

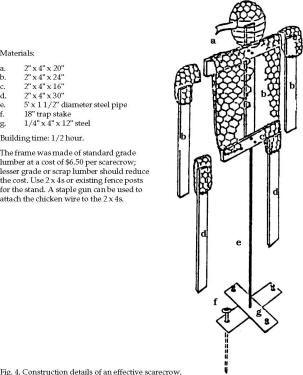

Scarecrows, made from 2 x

4-inch (5 x 10-cm) lumber and chicken wire (Fig. 4) and

dressed in pants or skirts, shirts, and hats, may keep

eagles away from an area for up to 3 weeks. The chicken

wire bodies allow the arms to wave in the wind. Clothes

can be purchased secondhand from Goodwill Industries for

about $3.50 per scarecrow. The frame is made of standard

grade lumber at a cost of about $6.50 per scarecrow; a

lesser grade or scrap lumber should reduce the cost.

Almost anything can be used as a stand, including 2 x 4s

or existing fence posts. The chicken wire is attached to

the 2 x 4s with a staple gun, which also comes in handy

for making field repairs. Building time is about 1/2

hour. Fluorescent orange paint can be sprayed on the

backs and chests of scarecrows and their arms hung with

shiny pans to increase visibility. Erect scarecrows on a

high ridge or point, where sheep and goats usually bed.

Most eagle predation occurs about sunup so the lambs or

kids will be close to the scarecrows during the time of

greatest danger. When eagles start to habituate to

scarecrows, harass them by shooting cracker shells near

perched or low-flying eagles. This activity will

reinforce the fear associated with humans and

scarecrows. A permit is required for such harassment. In

areas where ravens are common and preying on lambs or

kids, shooting or shooting at ravens keeps eagles wary

of scarecrows; again, a permit is required for this

activity.

Repellents No

repellents are registered or effective in reducing eagle

predation.

Toxicants No

toxicants are registered or permitted for use in

preventing or controlling eagle predation.

Trapping, Snaring, and

Shooting

Trapping, snaring, or shooting eagles is illegal,

except by permit. Regulations permit the Director, USFWS,

to issue permits for removal of depredating eagles

“under permit by firearms, traps, or other suitable

means except by poison or from aircraft.” However, by

policy of the Secretary, US Department of Interior, such

permits are not issued. The sole exception is very

limited live-trapping or net-gunning from a helicopter

and transplanting of eagles by USFWS and USDA-APHIS-ADC

personnel. Livestock owners who have, or suspect that

they have, eagle depredation should contact the USFWS or

USDA-APHIS-ADC for assistance and evaluation. Live

trapping and removal of depredating eagles by the USFWS

is permitted under certain conditions, and a limited

amount of such control is carried out. Net gunning from

a helicopter allows quick and selective removal of

depredating eagles from an area.

Economics of Damage and Control

Although eagles may

benefit producers by preying on rodents and rabbits and

feeding on carrion, they may have a major adverse impact

on individual producers by preying on young lambs, kids,

exotic game species, and other game animals. Losses are

most severe where nesting eagles prey repeatedly on the

same flock or where migrant eagles concentrate in an

area and cause major losses over a short period of time.

Whether eagle damage

control is necessary and beneficial depends on the

levels of loss, the costs of control, and the

effectiveness of control efforts for each damage

situation. The severe restrictions on the application of

any type of eagle control and the long delays in

securing the necessary permits and/or assistance from

the US Department of Interior are major constraints to

the protection of livestock.

Acknowledgments

Reviews and suggestions by

D. L. Flath, D. W. Hawthorne, G. L. Nunley, M. J. Shult,

C. W. Ramsey, W. Rightmire, and R. M. Timm were of major

help in the preparation of this manuscript.

Figure 1, bald eagle, from

Charles W. Schartz, Wildlife — Drawings, 1980, Missouri

Department of Conservation, Jefferson City, p. 53,

adapted by Emily Oseas Routman; golden eagle by Emily

Oseas Routman.

Figures 2 and 3 by Emily

Oseas Routman, adapted from Susan Brooke in US Fish and

Wildlife Service and Texas Agricultural Extension

Service (no date), and from Grossman. M.L. and J. Hamlet

(1964), Birds of Prey of the World, C.N. Potter, New

York, 496 pp.

Figure 4 by Daniel B. Pond

(1984), Montana Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit,

University of Montana, Missoula.

For Additional Information

Boeker, E. L. 1974. Status

of golden eagle surveys in the western states. Wildl.

Soc. Bull. 2:46-49.

Bruns, E. H. 1970. Winter

predation of golden eagles and coyotes on pronghorn

antelopes. Can. Field-Nat. 84:301-304.

Chamberlain, E. B. 1974.

Rare and endangered birds of the southern national

forests. US Dep. Agric. For. Serv., Washington, DC. 108

pp.

Crowe, S. 1980. Eagle

program annual report; fiscal year 1980. US Fish Wildl.

Serv., Div. An. Damage Control. San Angelo, Texas. 44

pp.

Foster, H. A., and R. E.

Crisler. 1978. Evaluation of golden eagle predation on

domestic sheep, Temperance Creek Snake Sheep and Goat

Allotment, Hells Canyon National Recreation Area,

Oregon. US Fish Wildl. Serv. An. Damage Control.

Portland, Oregon. 26 pp.

Glover, F. A., and L. C.

Heugly. 1970. Final report: golden eagle ecology in West

Texas. Colorado State Univ., Fort Collins. 84 pp.

Hogue, J. 1954. The grouse

and the eagle. Colorado Conserv. 3:8-11.

Kalmbach, E. R., R. H.

Imler, and L. W. Arnold. 1964. The American eagles and

their economic status, 1964. US Fish Wildl. Serv.,

Washington, DC. 86 pp.

Marshall, D. B., and P. R.

Mikerson. 1976. The golden eagle: 1776-1976. Natl. Parks

Conserv. Mag. 50(7):14-19.

Matchett, M. R., and B. W.

O’Gara. 1987. Methods of controlling golden eagle

depredation on domestic sheep in southwestern Montana.

J. Raptor Res. 21:85-94.

Miner, N. R. 1975. Montana

golden eagle removal and translocation project. Proc.

Great Plains Wildl. Damage Control Workshop 8:155-161.

Mollhagen, T. R., R. W.

Wiley, and R. L. Packard. 1972. Prey remains in golden

eagle nests: Texas and New Mexico. J. Wildl. Manage.

36:784-792.

Office of the Federal

Register, General Services Administration. 1978. Code of

federal regulations 50, wildlife and fisheries, US Govt.

Printing Office, Washington, DC. 842 pp.

O’Gara, B. W. 1982.

Predation by golden eagles on domestic lambs in Montana.

Pages 345358 in J. M. Peek and P. D. Dalke, eds. Proc.

Wildl.-Livestock Relationships Symp. Proc. 10 Univ.

Idaho, Moscow.

O’Gara, B. W. and D. C.

Getz. 1986. Capturing golden eagles using a helicopter

and net gun. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 14:400-402.

Olendorff, R. R., A. D.

Miller, and R. N. Lehman. 1981. Suggested practices for

raptor protection on powerlines. The state of the art in

1981. Raptor Res. Rep. No. 4. Raptor Res. Found., Inc.

111 pp.

Phillips, R. L., and F. S.

Blom. 1988. Distribution and magnitude of

eagle/livestock conflicts in the western United States.

Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 13:241-244.

Phillips, R. L., T. P.

McEneany, and A. E. Beske. 1984. Population densities of

breeding golden eagles in Wyoming. Wildl. Soc. Bull.

12:269-273.

Snow, C. 1973. Habitat

management service for endangered species. Rep. No. 5,

southern bald eagle and northern bald eagle. US Dep.

Inter., Bur. Land Manage. Portland, Oregon. 58 pp.

US Fish and Wildlife

Service. 1976. Taking of golden eagles: denial of

depredation control order. Federal Register

4(221):50355-50356.

US Forest Service. 1977.

Bald eagle habitat management guidelines, US Forest

Service— California Region. US For. Serv. San Francisco,

California. 60 pp.

Wade, D. A., and J. E.

Bowns. 1982. Procedures for evaluating predation on

livestock and wildlife. Bull. B-1429, Texas Agric. Ext.

Serv. College Station. 42 pp.

Editors

Scott E. Hygnstrom; Robert

M. Timm; Gary E. Larson

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF

WILDLIFE DAMAGE — 1994

Cooperative Extension

Division Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources

University of Nebraska -Lincoln United States Department

of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service Animal Damage Control Great Plains Agricultural

Council Wildlife Committee

Special

thanks to:

Clemson University

|